Publishing Frontier’s offtake agreement template

August 15, 2024|Hannah Bebbington

Frontier is an advance market commitment to buy permanent carbon removal that will be delivered this decade. We launched in 2022 with the goal of signaling to entrepreneurs and investors that there is at least $1B of revenue for carbon removal companies, if they can build and deliver. The idea is that by being willing to be early customers for new technologies, we can help carbon removal scale faster. But for this commitment to have the catalyzing effect we hope it will, we need to make good on it: committed funds need to be signed into actual ink-and-paper contracts between specific buyers and suppliers.

This sounds simple enough: write a contract to buy X tons of carbon removal at Y price for Z years (often referred to as an ‘offtake agreement’). There are standardized, public contracts that do this for things like renewable energy or commodities. Most public contracts that exist today are designed to support technologies that are technically mature and already have a large market. However, carbon removal is still nascent—the technologies are much earlier, and the confidence in the market (especially when prices are high) is low. And yet, in order to get carbon removal to the scale scientists say we need, we have to start building—and learning—now. Carbon removal suppliers need offtakes today to help get new projects off the ground. So, the offtake agreements themselves need to be designed to work for carbon removal at its current stage, and thus manage more risks and unknowns than the existing contracts contemplate.

In order for an offtake with an early-stage carbon removal supplier to be catalytic, it needs to be:

- Bankable for project financiers, despite these technologies being very early: Project financiers need to know buyers will pay for the tons, so long as the supplier delivers. The revenue needs to be predictable and the risk of unexpected terminations very low. True bankability actually depends on project financiers getting comfortable with the technology risk, the execution risk, and the market risk associated with a project. Our goal with these documents is that these offtake agreements are robust enough to retire the market risk entirely, if 100% of the volume is contracted on this paperwork. Technology and execution risk have to be managed in other ways.

- Flexible enough for early-stage suppliers, given building things is hard: FOAK project developers are, by definition, building something new. It can be hard to predict exactly how a project will develop. Suppliers need upfront alignment with buyers on which project details matter and they need generous and flexible expectations from buyers on delivery delays and shortfalls.

- Attractive for early buyers, despite there still being unknowns about the project at the time of signing: Given the potential risk and uncertainty in these projects in the early stages, contracts need to protect buyers from buying carbon removal that doesn’t meet their specifications. Ideally, contracts also provide some incentive for early participation, like getting access to future, cheaper volume.

We’ve edited and refined our template over the course of seven offtake deals and ~$300M+ contracted. Today we’re publishing it in its current form, along with some notes on the core components of the document as well as some lessons learned along the way. This template is very unlikely to be the final form of carbon removal offtake agreements, but our hope is that it may help other teams save valuable time by providing a decent starting point.

The Frontier offtake agreement

Below we walk through the Frontier offtake agreement to show how we try to translate these goals into an actual contract. We’ll do this in three parts.

- First, we’ll lay out the timeline of a typical carbon removal project—this context is important for understanding how key contract dates map to what’s happening at the project level.

- Second, we’ll walk through the key concepts in the contract.

- Third, there is a link to the template itself where you can see how the key concepts show up in the contract. If you want to skip ahead to the template, you can do that here.

Timeline

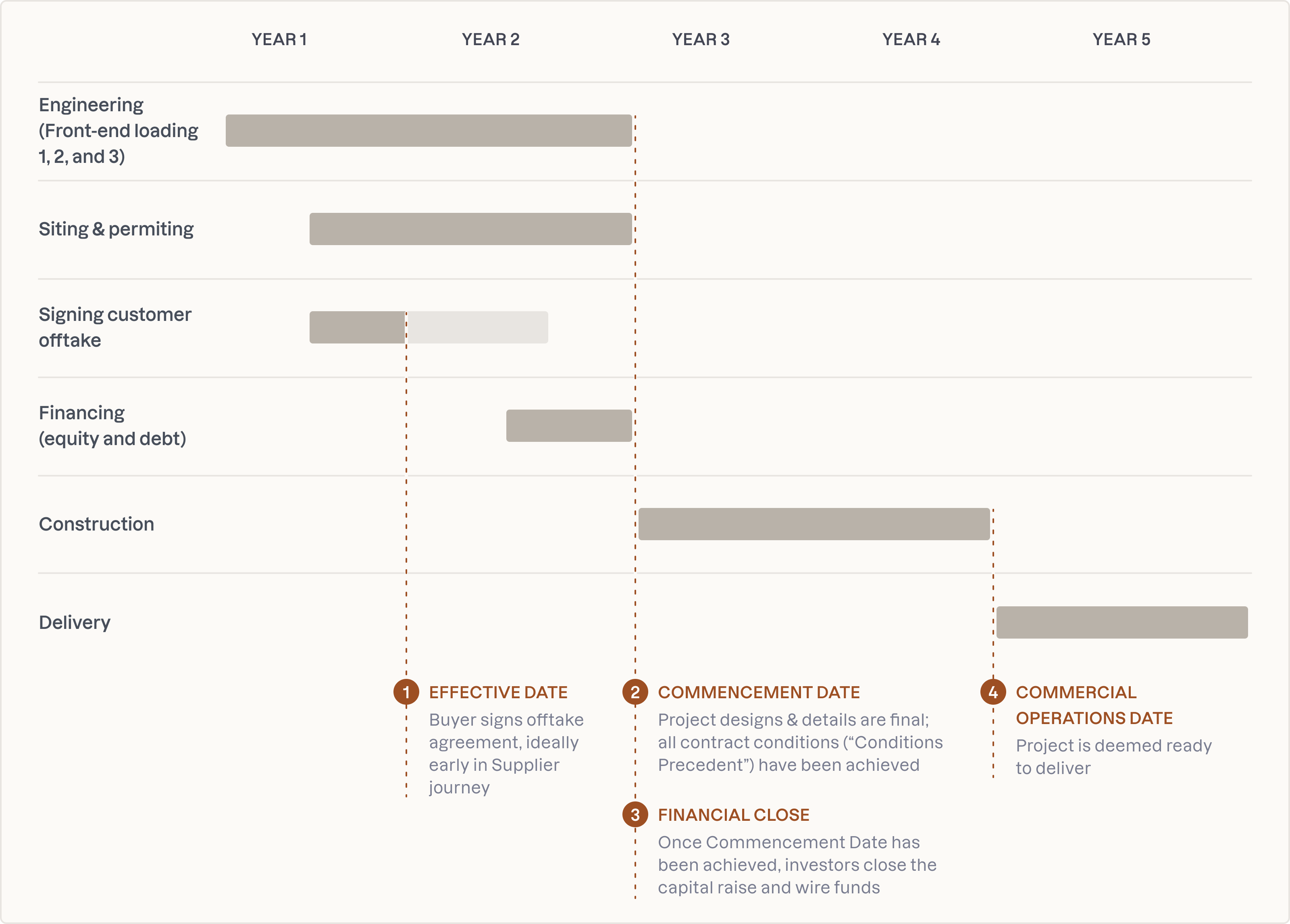

The structure of the offtake agreement is designed to map to the stages of a project’s build timeline:

- Effective Date: The Effective Date is typically the day the agreement is signed. This is ideally as early as possible in a project’s journey so that suppliers can leverage it to open discussions with financial backers and other offtakers.

- Commencement Date: Between the Effective Date and the Commencement Date, the supplier is finalizing the details of their project, such as completing engineering designs, securing their site permits, putting their energy source in place, etc. Some of these outstanding details are the “Conditions Precedent” in the agreement, meaning they must be demonstrably met and approved by the buyer before any delivery can happen. These are particularly useful for buyers who are committing to a project early and want confidence they’ll know how a project will develop. After the resolution of each outstanding item, the Commencement Date is met and the buyer is committed to paying for the carbon removal units (CRUs) when delivered according to spec.

- Financial Close: Most project financiers will take the final investment decision on a project and transmit funds after the Commencement Date has been met. This is done so that the project financier can minimize the capital at risk while the team is still developing project specifications. Once a supplier receives the funds for their project, they can begin construction.

- Commercial Operation Date (COD): When construction is complete, the project will achieve their Commercial Operation Date by demonstrating they can operate and deliver as expected.

- Delivery: Once both the Commencement Date and COD have been met, the supplier can start delivering CRUs to buyers and buyers must pay for what is delivered, per the terms in the agreement.

Key contract concepts

Here we’ll walk through the key concepts that make our offtake agreement what it is and why we need each one. If you click “view in template” in the left-hand column, you can see these concepts in-situ in the agreement with additional commentary.

| Key concept | What it is | Why we structure it this way |

|---|---|---|

Fixed price & volume | The Frontier offtake agreement has a straightforward take-and-pay structure with a fixed price and volume. There are other alternative structures that work in different use cases—such as hell-or-high-water or contracts-for-difference–that may be worth considering depending on the specific goals of the buyer. |

|

Project Description | This agreement requires that the supplier operate the project in a way that aligns with buyer expectations. The supplier and buyer typically work together on this product spec to describe the technology being used and anything else that may be important for the buyer (e.g., the type of biomass feedstock sourced, the type of energy used to power the facility, the site(s) that will generate the CRUs, etc.). The buyer is only on the hook to pay for CRUs that meet this description. |

|

Conditions Precedent & Commencement Date | This agreement lists Conditions Precedent that must be met in order to deliver CRUs. The date at which all these conditions are met is the ‘Commencement Date.’ This list of conditions encompasses all the outstanding questions that may impact the supplier’s ability to operate the project as the buyer expects, and that the buyer wants to review and approve before delivery begins. Some of them are standard across all projects (e.g., the need for an approved Protocol and CRU Issuer) while others are project-specific (e.g., securing a site permit or meeting a technical development milestone). These Conditions Precedent ensure the project is developing in accordance with buyer expectations. |

|

Commercial Operation Date | To the extent the supplier is building a facility that requires construction, a Commercial Operation Date (COD) is useful. This is the date at which the facility is ready and able to start delivering CRUs to the buyer that adhere to the Project Description. For projects not building a facility, often the Commencement Date (outlined in the previous key concept) is sufficient to start delivery. |

|

Delivery | A CRU in this agreement is considered delivered when the buyer receives:

At the point of Delivery, the buyer takes title to the CRU. |

|

Delivery shortfall & delays | The supplier can under-deliver proportionately to each buyer, so long as they exceed the Minimum Quantity (a percent of the total contract volume) in or by a certain year. If they don’t exceed this Minimum Quantity, there are simple termination rights for the buyer, but no damages. The supplier can also get an additional six months to meet the Commencement Date if the delay is explained to the buyer (plus up to an additional X months at buyer's discretion). |

|

Termination rights | Buyers have limited termination rights. They can terminate only:

|

|

Remedies | We limit punitive damages. If a project is demonstrably not going to work, we prefer to part ways quickly and kindly, without damages. Monetary damages are used sparingly and only where there is bad behavior or real injury to buyers. If a supplier acts in bad faith—e.g., delivers invalid tons, doesn’t offer the expected ROFO—there are specific remedies outlined to make the buyer whole. |

|

Protocol & credit issuers | A Protocol is the set of requirements used to measure the carbon removal being delivered. A Credit Issuer is the third-party entity that will verify the credits meet the Protocol and list them on a public registry. Both must be approved by the buyer as part of the Conditions Precedent to the Commencement Date. Once a project starts delivering, a supplier, buyer or Credit Issuer can request a change to the Protocol. The parties will confer on whether the change is advisable to ensure accurate verification and quantification of the CRUs. If the change is put forth by the CRU Issuer, the buyer can approve it. Otherwise, the parties have to mutually agree on a path forward. Note, this agreement does not anticipate that the price or quantity will be adjusted in the agreement as a result of a change to the Protocol. |

|

Right of first offer | This Agreement gives the buyer a right to buy excess tons produced by the project delivering on this agreement and future tons delivered from new projects owned by or affiliated with the supplier. To make this fair and practical for the suppliers, we structure this as a right of first offer (ROFO), not refusal, so there can’t be an endless hold-out on volume. Additionally, the future tons offered are done so at a price and terms put forth by the supplier. |

|

There are some terms that are common in standard offtake agreements in other industries that are not included in our template. We thought it might be helpful to lay out our rationale for not including them. However, it is reasonable to expect that some of these terms could make sense in other categories of novel climate technologies or start to appear in more carbon removal agreements as the market matures:

- Security: It is common for large renewable energy developers to be required to provide security or collateral that demonstrates they could cover their obligations or any liabilities if the project isn’t successful (for example in the form of a letter of credit, a guarantee from a parent entity, or a pledge of its interest in certain project assets). We do not include this requirement in our carbon removal contracts because: (1) we seek very limited punitive damages in our contracts, and (2) our counterparties are often small startups who wouldn’t be able to provide security without a lot of time, energy, and extra funding. Note, for any project where the offtake is for a physical good that is being actually used for something (e.g., concrete or steel to build a building), security could certainly make sense, even for novel technologies.

- Guaranteed volumes: It is common for large renewable energy developers to guarantee volume (i.e., if their project is unable to deliver the required volume under the agreement, they will source from other projects). While this is workable in the renewable energy space, the carbon removal market is still a nascent market, so there is not a liquid market to source from, and we are only interested in buying from specific carbon removal technology types (CRUs are not interchangeable). We’d rather just reallocate the capital to a project of our own choosing.

- Liquidated damages: Liquidated damages are pre-defined damages, often paid by a supplier to the buyer in the instance of a delay or delivery shortfall. These are often specifically denominated in a $/unit, for example $/hour or $/MWh. They are meant to offer a way of aligning at the outset how to quantify what damages a party might suffer in a certain scenario. We do not include these types of contract damages in our offtake agreement because the real damages a buyer faces in a shortfall or delay scenario are very limited. For physical commodities, especially those with existing spot markets and lots of price visibility (like concrete), these may be required.

- Delivery insurance: A number of insurance offerings have emerged in the carbon removal market to protect both buyers and suppliers in the instance of a delivery shortfall. Similar to insurance products in the renewable energy space, these products build confidence that participating parties are ‘covered’ even if the technology doesn’t work, the facility is delayed, or an unexpected event occurs. Some of these products compensate a buyer to replace undelivered credits or cover costs to find additional credits if a supplier doesn’t deliver. However, a policy may also insure the supplier, giving project financiers more confidence a supplier will have the resources to cover their debt payments even in the absence of credit sales. These products are nascent and we did not need any insurance to get all stakeholders to the table, and so the concept is not included in our template.

The offtake agreement template

View or download the full template. We’ve annotated it with the key concepts outlined above to make for faster reading.

See the template

Lessons

Some things we wish we’d known earlier:

- Make sure both business and legal teams are engaged in the agreement drafting from the start. When writing contracts for nascent technologies, few issues can be easily categorized as either “business” or “legal”. Business leads need to get comfortable talking about provisions like limitations on liability and assignment, and lawyers need to understand how the technologies work and what the risks are so they can work together to design around the fact-specific nature of the deal.

- Have at least one dedicated lawyer on your team. When we got started, we had 1 in-house lawyer and 1-2 partners at a law firm supporting the drafting of the original template and negotiations of the first few deals. It was important to have sustained support from people who weren’t just focused on getting a single deal over the line, but who could also see how our offtake agreements looked in aggregate and how agreements were performing in the field. Our lawyers were able to incorporate lessons across negotiations and maintain a single style across our documents.

- Rewrite agreements often to streamline & simplify. Our first contract started with the bare minimum and, with input from others, slowly came to include the kitchen sink. Buyers, lawyers, suppliers, and investors added provisions to account for every possible edge case. The document became over-complicated, hard to parse and, most importantly, intimidating to parties who worried the density was masking ‘gotchas’. So we took that ‘Frankenstein-ed’ document and had a single lawyer rewrite it, capturing the key points from the original negotiations, but in a streamlined and simplified form. This cut negotiations from six months to two months. Limit the number of lawyers who have the ‘pen’ and rewrite in plain english as often as possible.

- Get all relevant stakeholders, even those who aren’t signing, to give feedback on the terms. For example, project financiers are an important audience for these carbon removal projects. They are the ones who will provide the capital to build the projects that will deliver on these agreements, so it is important that these agreements work for them (in other words, it’s important the form is ‘bankable’). When figuring out who needs to be in the room, make sure you understand the whole ecosystem of stakeholders who care about this agreement (whether signing or not) and get them actually in the negotiations early. For other climate technologies, this could include homeowners, landowners, or regulators, to name a few.

Whether you’re working in carbon removal, thinking about building another AMC or scaling other novel climate tech, we hope this template saves your team valuable time. Please reach out to us at info@frontierclimate.com with any questions.

A special thank you to Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliff LLP for the expert insight provided during the drafting and negotiations of this template.

Disclaimer: The offtake agreement template is intended to serve as a starting point only and should be modified to meet your specific deal and organization requirements. The offtake agreement template and related annotations do not constitute legal advice.